Something I’ve been thinking about lately: to what degree are the skills we develop to play games transferable from one system to the next? Obviously there are some that are 100% transferable without requiring adaptation. Probability in dice games, for instance, is such a skill. The odds of an outcome don’t change based on what game you’re playing if your target in either system is some number on a six sided die. On the other hand, trying to perform a qualitative analysis of some component in Game X based on your understanding of Game Y is more complicated for a number of reasons. That being said, the properties of a given pair of games might have enough overlap that generalizing some of our understanding of one will provide insight into optimal play or option choices in another.

Quadrant TheoryPermalink

I’ve said it before, but as a long time Magic: the Gathering player, I’ve consumed hundreds of thousands of words worth of content aimed at becoming a better Planeswalker. One concept that I came across late in my active competitive “career” such as it was, is the idea of Quadrant Theory. Attributed to Brian Wong, Quadrant Theory is the idea that there are essentially four game states that can occur in Magic. They are:

- Developing: The opening moves of the game, in which players deploy resources and try and generate an advantage before advancing toward their win conditions.

- Parity: The game is at a stalemate, and both players are waiting for something to happen that breaks the game open.

- Winning: You are ahead, and if nothing changes, will win the game shortly.

- Losing: You are behind, and if nothing changes, will lose the game shortly.

The core principle of Quadrant Theory is that for a card to be great, it should perform well in more than one of the four possible game states. An example of a card that’s great in almost any situation would be a removal spell that cheaply kills an opponent’s creature. Such a card is good early (if your opponent tries to pull ahead with a cheap creature, you can kill it), good at parity (you can destroy an opponent’s creature to enable a profitable attack), good when you’re winning (your opponent has to draw two creatures to stabilize the game), and good when you’re losing (helps you stabilize the game before your opponent runs away with it).

All four quadrants are linked to Magic’s core mechanic of drawing game pieces from a randomized deck. ASOIAFTMG also features a randomized deck, and while that deck doesn’t make up the entirety of the game the way it does in Magic, it does create the opportunity for the game state to change wildly based on random inputs in a way that’s distinct from dice rolls as units engage in combat. My intuition is that there are enough similarities between Magic and ASOIAF that we can actually adapt Quadrant Theory to a degree when analyzing our choices at list building.

How does Quadrant Theory apply to ASOIAF, though? First of all, it has to be said that it’s not a perfect 1:1 translation. ASOIAF games do not develop the same way with raw resources deployed to pay for adding new components to the game. Instead, the game state - the position and health and relative value - of units, or the Tactics Cards you’ve played, or the orders or limited-use abilities you have access to - is relatively static until players begin to take action against one another. The “Developing” quadrant therefore in ASOIAF isn’t really about resource acquisition and deployment, it’s about positioning. Here I think there’s another type of game that we can borrow a concept from to make a more complete vision of ASOIAF’s game quadrants: fighting games.

HADOUKENPermalink

Fighting games - from the venerable 2D (in terms of gameplay) fighters such as Capcom’s Street Fighter or SNK’s King of Fighters series to 3D fighters like Tekken - all share some core concepts in their design. One of those concepts is the idea of a “Neutral Game”. In a fighting game, characters are often for a variety of reasons unable to respond to inputs. They might be locked in to an attack or jump animation that must complete before a new command will execute, or maybe in a hit or block ‘stun’ state in which they cannot move for a certain small amount of time after an opponent’s attack lands. Any situation in which both characters are free to move and act as they choose is referred to as “Neutral”. As the play-by-play announcers in Street Fighter 6 are keen to remind the player, a solid neutral game wins matches.

I think the similarity between this idea and the way melee combat works in ASOIAF is pretty obvious. When two units attack one another, those units become engaged, and their movement options are restricted to realigning for another attack, or retreating. That’s very similar to what happens in fighting games - when one player or the other tries to advance the game state toward their win condition, both players suffer a reduction of available choices in exchange for an opportunity to deal damage to their opponent. The aggressor usually has an advantage when the game advances past Neutral, because their moves create pressure that the defender must respond to or get blown up by a damaging combo. So too in Song - whoever gets the first charge is usually at an advantage unless a card or effect can somehow punish that aggressive move. The similarities between this completely separate genre of game and ASOIAF don’t end there, but the primary thing I’m interested in is stealing the idea of “Neutral” as a game state, to replace “Developing” in our ASOIAF quadrant theory.

Another thing that needs to be accounted for is the relative rarity and brevity of the “Parity” state in most games of ASOIAF. The fact is, it’s difficult to completely quantify when a game in this system is truly “at parity”. Number of wounds on the table, total activations, activations remaining, who is first player - all of these things have an impact on the game state, and they will add up more often than not to one player having a measurable advantage over the other. That being said, while the game might not be truly stalemated, it might be very close. So instead of “Parity”, let’s call the “in progress but undecided” game state “Contested”. Combat has started in earnest, but there is not yet a a clear victor or expected winner.

With these amendments, I think the following four game situations in ASOIAF should form the basis of our evaluation strategy:

- Neutral: Few or no units are engaged in melee combat. Both players are mostly free to maneuver all of their forces as they see fit.

- Contested: Combat is occurring in one or more places on the battlefield, but neither player has amassed a significant advantage.

- Winning: You are ahead, and if nothing changes, will win the game shortly.

- Losing: You are behind, and if nothing changes, will lose the game shortly.

ApplicationsPermalink

Let’s take a few examples and examine them through the lens of Quadrant Theory as we’ve amended it for ASOIAFTMG. I’m confining all of these to House Stark, since that’s the faction that I am most familiar with - I’d be very interested to see people walk through examples in their faction of choice and try and figure out if this approach provides any insight into what makes a “good” unit, or card, or attachment. First, we’ll take a look at a couple of Tactics Cards, then a Non-Combat Unit, and finally a Combat Unit.

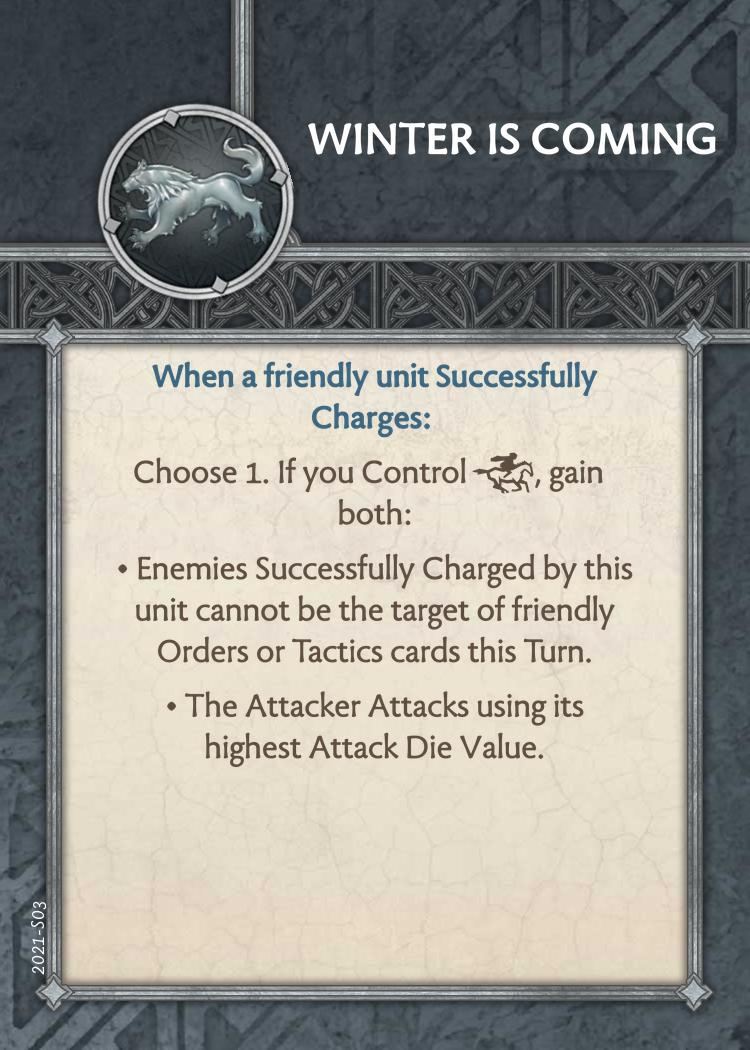

Winter is ComingPermalink

Winter is Coming was changed in the Season 3 update, and my impression based on discussions on various Discords and at tournaments with other Stark players is that overall it’s acknowledged now as being one of our more important cards. This is thanks mainly to the fact that it no longer shares a trigger with Devastating Impact. Let’s analyze this with our newly minted framework.

Neutral: Winter is Coming’s effect is primarily for ending the Neutral game state by ensuring that a Charge isn’t subject to a reversal or serious mitigation from a reactive order or card play by the defender. On a letter grade scale, I’d call it a B+ in Neutral, because it ensures that you exit that game state with the advantage of shutting down defensive options. There’s also some synergy here with a couple of Stark units (Umber Berserkers, Umber Ravagers) out of Neutral, allowing them to roll their maximum dice with their inverted melee decay profiles.

Contested: C. Once the bulk of each players units are locked up in combat, Winter is Coming may do literally nothing. On the other hand, in a brawling situation, a unit that is injured and can disengage safely then charge back into combat can benefit significantly from both of these effects.

Winning: C. Situationally Winter is Coming can make a cleanup charge into a second engagement safer, but generally isn’t important in this game state.

Losing: C. Again, only situationally useful in the mid-to-late stages of a game, barring very specific circumstances.

So a B+ in Neutral, and a C otherwise. While Winter is Coming is a very important piece of the Stark gameplan, it’s important to be realistic about just how situational the card is. You will not always hang on to this one - sometimes it’s correct to toss it and keep drawing cards.

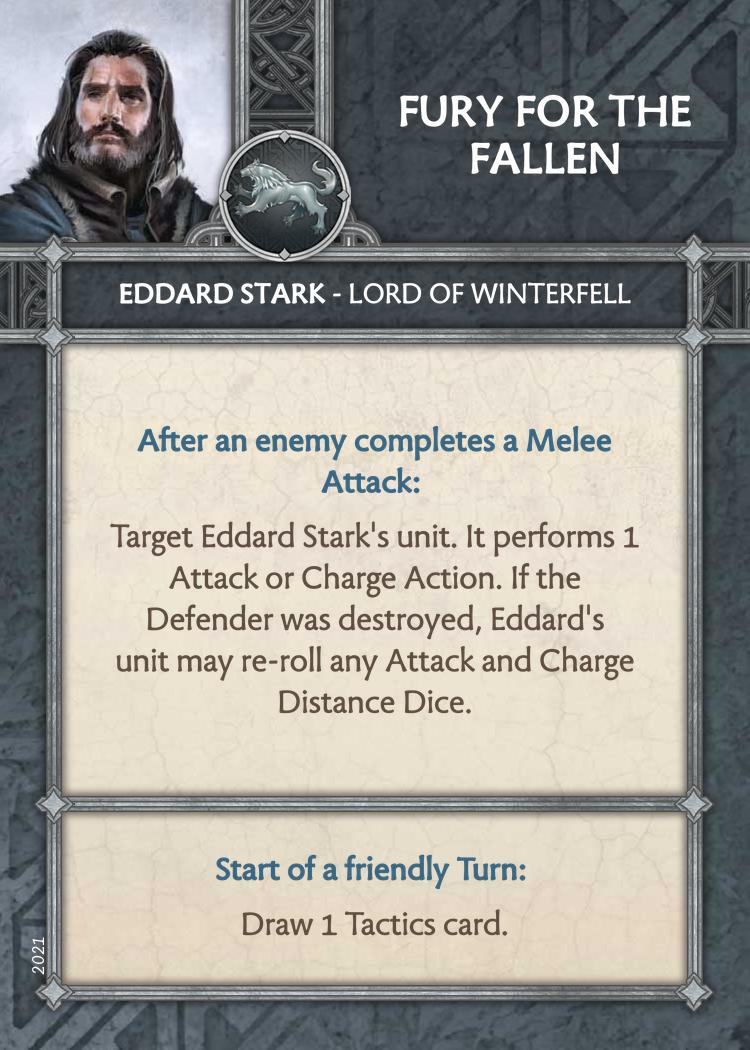

Fury for the FallenPermalink

Fury for the Fallen is Eddard Stark’s marquee Tactics card. It provides an out-of-sequence additional attack or charge action (one of the most powerful types of effect in the game) for Eddard’s unit, and if that’s for some reason not what you want, can be discarded to draw a new card. “Draw a card” are what I consider to be the three best words in gaming, so I’ll admit I’m pretty biased in favor of this card before we even get started with our Quadrant analysis.

Neutral: If it weren’t for the secondary clause, this would be a D. Fury does nothing at all until someone has exited Neutral, with the possible exception of creating a powerful reversal if the opponent can be baited into a charge that looks attractive but for the fact that it’s granting Eddard’s unit a free counter charge. With the “Draw a card” clause, it’s at least a C+ in Neutral simply for the fact that it gives you a chance to dig to an effect that might have a more immediate impact on the game. Of course whether or not that’s really a good idea will depend on your list and the game state, but having the option is worh something.

Contested: A+. Eddard engaged in combat with Fury in hand is a very dominant position. Your opponent must either retreat or attack, and neither of these are good choices in the face of Fury for the Fallen.

Winning: A+. For the same reason the card is an A+ when the game is contested, it’s extremely good when you’re ahead. Your opponent can’t win by not-attacking, which means it’s even easier to force punishable situations with this card.

Losing: B. If your opponent is winning by a significant margin, they may elect to play around Fury for the Fallen (assuming Eddard is still alive) by retreating more and attacking less. If Eddard is dead already, the only value you get here is by cycling it to draw deeper into the rest of your deck.

Considering the power level of this card when the game is Contested, the impossible situations it can create for your opponent when you’re winning, and the basic utility of having the secondary “draw a card” clause on it, Fury for the Fallen is a compelling argument for why you might choose Eddard Stark as your commander. It’s good in three out of four quadrants, but the secondary effect means it’s never a totally dead draw.

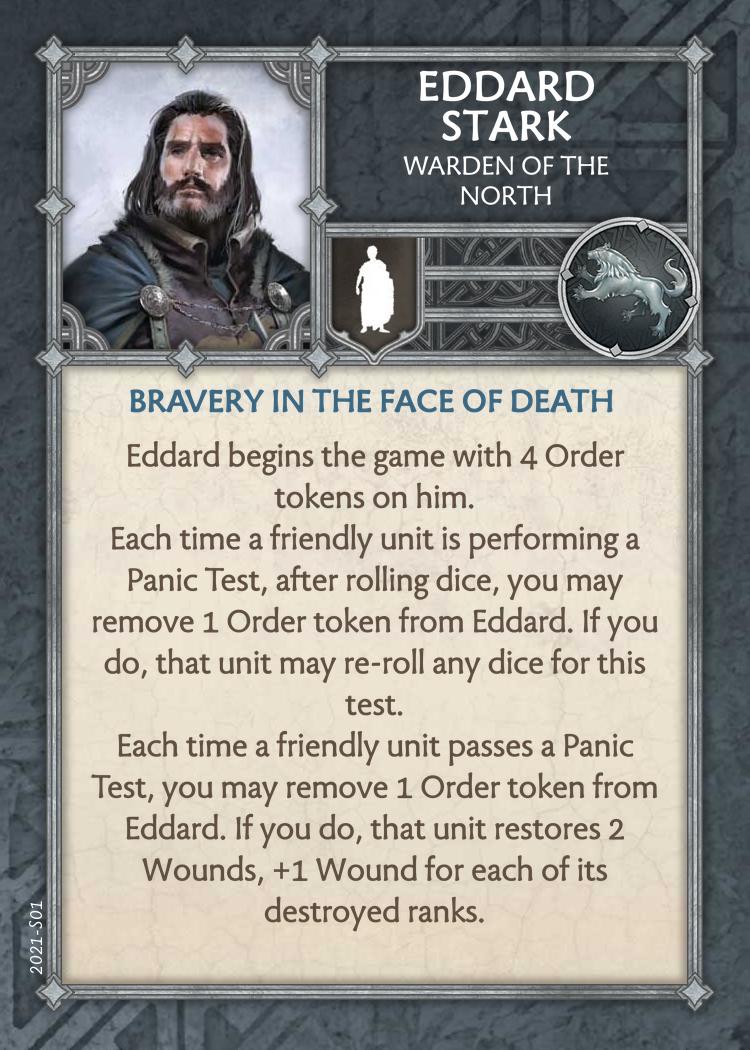

Eddard Stark - Warden of the NorthPermalink

Eddard 6 has seen a resurgence of play with the addition of pass tokens in Season 3, as Stark players felt they were able to move away from “8+ activations or lose” list building for the first time in a long time. Paired with the rework of Tully Cavaliers, this version of Eddard has been a mainstay in winning Stark lists since the beginning of Season 3. Season 4 has opened things up again such that House Stark might return to a higher activation count play style, but I don’t see WotN going away any time soon. What is it exactly that makes him so good? Let’s see if we can figure it out.

Neutral: F-. Eddard doesn’t contribute to the Neutral game even slightly. Does literally nothing.

Contested: Best in Class. Valedictorian. Early university acceptance with a full academic scholarship. Why? Because Eddard’s entire suite of abilities is about ensuring that the opponent cannot advance the game past the Contested state and start winning it. The healing that this NCU can produce undoes your opponent’s hard work, allowing you to grind away at their resources activation by activation, and it does so without requiring that you yourself take any action apart from spending tokens.

Winning: A or A+. Your opponent isn’t going to be able to easily improve their situation if they have to interact with Eddard’s effect, which means you stay in the drivers seat.

Losing: B- or C+. Again, Eddard’s effect tends to freeze the game in whatever state it’s at, but it can’t by itself win for you. At best it helps you lose slower, meaning you have opportunities to claw back into a winnable position. Usually you won’t be in this position unless Eddard is out of tokens, though.

The absolutely absurd power of Eddard 6 in the Contested stage of the game makes him a powerhouse in the faction, especially when combined with Rally Banner. In some game modes he can also directly translate to extra VP scored by rerolling Panic tests to hang on to objective tokens. Just a very strong tool for slowing the game down.

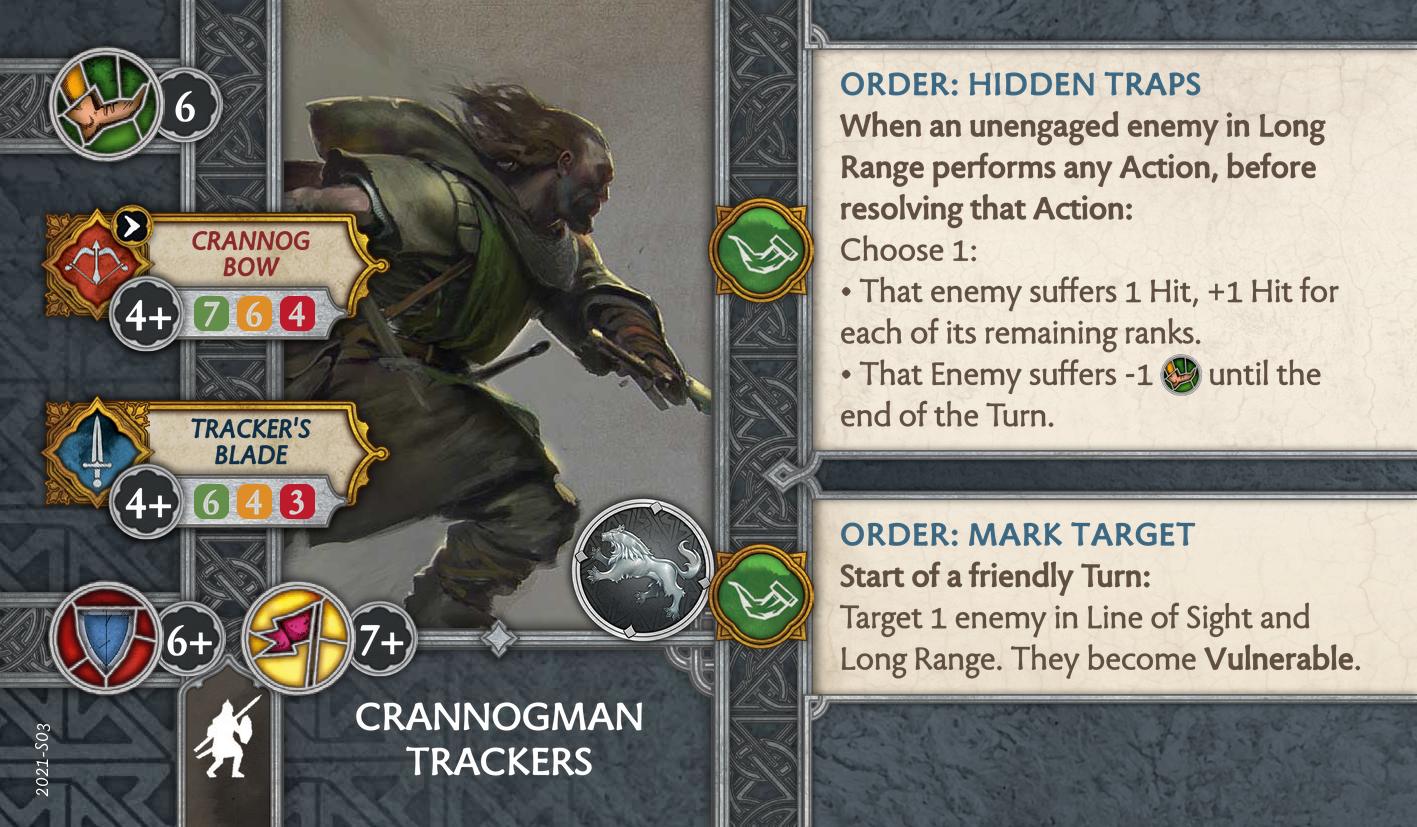

Crannogman TrackersPermalink

Oh my sweet swampy boys. The Trackers were already a sleeper pick for best unit in the faction before being glowed up in Season 3 with the addition of Mark Target. They are poised to continue being a great support unit with a high impact on the faction’s listbuilding. Let’s look at why.

Neutral: A+. Crannogman Trackers are the kings of the neutral game state. They provide value against anyone that acts within long range, either in the form of damage or by hampering their movement with Hidden Traps. In some situations they can even close into shooting range and start to deal direct damage with attacks thanks to their own 6” speed. With apologies to readers that have never played Street Fighter, this is like Guile holding down-back in the corner, throwing out Sonic Booms and waiting for the jump in to punish with a Flash Kick. You can’t safely approach, and if you stand at range doing nothing, you lose.

Contested: B. Trackers themselves don’t (usually) want to be engaged, but the work they did in the neutral stage of the game translates to an advantage in this one thanks to the chip damage from Hidden Traps. More impactful at this stage however are the repeated Vulnerable tokens they hand out, as well as the fairly easy and safe to achive flank shots they line up to supplement the damage of your melee units that are tying up the opponent’s front line.

Winning: B. If you’re ahead with some Trackers on an objective that your opponent has to walk toward in order to turn things around, you’re in good shape to hang on to your lead so long as you keep them alive and scoring.

Losing: C. It’s quite difficult to mount a come-from-behind victory with only a single unit of Trackers left to your name, but they’re not toothless.

It’s easy to see the role Trackers play in Starks. Dominating the early game, they force the opponent to take sometimes significant damage merely to approach into their own effective range, which unfortunately also happens to be the effective range of every other tool in the Stark arsenal.

All Squared UpPermalink

Whether or not you specifically agree with this method of evaluating your options at list building, I hope it’s given you some food for thought. Taking a step back and considering the tools we have at our disposal for making decisions in the games we play can yield some great results as our understanding of the underlying mechanics and systems grows. I’ve personally found this approach to be useful in quickly finding the best option among a set of competing choices, and I expect that others will too.

Until next time,

CRAIG